-Stage 4.5.2-

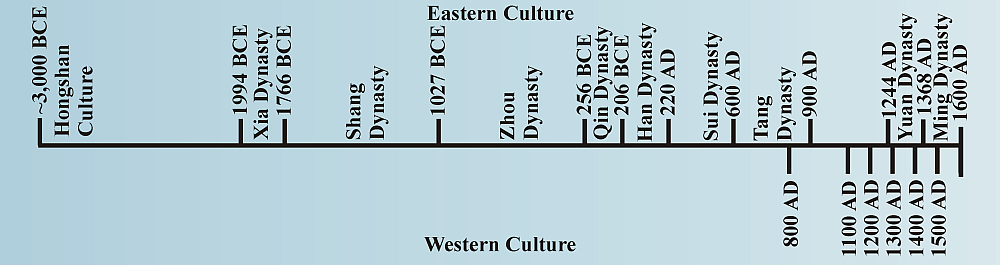

DINOSAURS! From Cultural to Pop Culture

"Medieval Times: The Age of Dragons"

One of the hallmarks of the Medieval time period was, of course, dragons, and the knights that rode in to slay them. Beowulf was one of the first pieces of literature to present the dragon, along with the now synonymous fire breathing aspect of it. However, long before Beowulf was a gleam in his author's eye, the dragons of the "East" were dominant. The origin of Eastern (or Chinese) dragons is also unknown, like the Western (or European) dragons. Based on the number of fossils that have come out of China and the surrounding regions there is a possibility that they helped to shape the future of what dragons eventually became (New World Encyclopedia).

There are as many stories about how the dragon came to be (as you can imagine from a culture where the dragon is as deeply imbedded as the Chinese culture is). Here are just a couple of them:

There is a theory that the Eastern Dragon is a conglomeration of many animals into one "super beast". The theory is that six to seven thousand years ago early Chinese people believed that certain animals and plants possessed the power to overcome nature's fury. Different tribes would adopt a different animal, or totem. One tribe, ruled by the legendary Emperor Huang Di (the Yellow Emperor), used the snake as their totem and as they conquered other tribes they would acquire their totem and merge them with the snake. Eventually the dragon was born with the head of a camel, horns of a deer, eyes of a hare, ears of a bull, neck of a snake, belly of a clam, scales of a carp, claws of an eagle, and paws of a tiger (PrimarySource.org).

Another dragon origination theory suggested by the archaeologist Zhou Chongfa was that the initial inspiration for the dragon was lightning. The Chinese pronunciation of the word dragon "long" resembles the natural sound of thunder. This theory combined the early settlers need for water and the relief that the lightning provided as it was intricately linked with the much needed rain (People's Daily).

Is there any proof that dinosaur skeletons influenced the historical creation of dragons, No. But the possibility is there. This is something that will never be disproven or proven, the evidence just doesn't exist either way. So I say, let's just have fun with it and explore the "evolution" of the Chinese dragon through time.

The Zigong Dinosaur Museum, Zigong, China (CNN)

Disclaimer: Unfortunately trying to find legitimate images of ancient Chinese dragons is near impossible on the internet with the plethora of Pinterest posts that don't actually link to anything, rampant auction sites with their often dubious claims of authentic dates (and personally I can't condone the selling of ancient pieces of history, "It belongs in a museum!"), or Creationist websites with their own variety of distorting the facts. I tried my best to filter out those images, and only focus on the ones I could determine were seemingly legitimate dragons representations dating to the time periods represented.

That being said, let's look at dragons through history:

~3000 BCE (Before the Common Era)

Hongshan Culture

One of the earliest known physical depictions of a dragon. This Hongshan culture "C" shaped plate of a dragon (showchina.org) looks like many of the early dragon forms which are termed the "pig" dragon. Pig dragons are dragons with pig-like heads and snake bodies, often coiled up in some manner.

Xia Dynasty

One of the earliest dragon sculptures ever found. This dragon sculpture is made of over 2,000 pieces of turquoise from Erlitou, which was possibly the capital of the Xia Dynasty (china.org.cn)

Shang Dynasty

Shang Dynasty "pig" dragons (chaz.org).

Zhou Dynasty

Early Eastern Zhou dragons (chaz.org). In these I feel the dragon shaped head is starting to progress to the stereotypical dragon we know of today.

Qin Dynasty

Qin Dynasty bronze dragon design - Shaanxi History Museum, Xi'an, China (travelblog.com). Here I feel we have more snake-like representations than many of the previous forms.

Han Dynasty

Han Dynasty stone relief engraving showing a form of Dragon Dance (Wikipedia). This is the first time where a dragon has been depicted having limbs. Previous dragons all had a rather snake-like representation and here we are starting to get more of a mixture of animals. The Dragon Dance is the dance often seen in parades where many people dress up inside a giant dragon and dance/march down a street.

Gold hook buckle with jade dragon, Western Han dynasty, from the mausoleum of Nanyue King Zhaomo, Xianggang, Guangzhou - Hong Kong Museum of History (Wikimedia.org).

It appears that at about this point in history, we move away from the generic "pig" dragon, with a pig head and snake body, into one that is much more detailed with many of the now iconic features of the Chinese dragon, such as the fish scaled body, clawed arms, and the now famous dragon head.

Sui Dynasty

Model of a Sui Dynasty dragon boat (cultural-china.com).

Tang Dynasty

Gilded bronze dragon from the Tang Dynasty (cultural-china.com)

Close up of the head (Art Gallery NSW).

From this point on, I feel we have reached a modern dragon, at least in the Chinese culture.

Although created first, there is little evidence that the Chinese dragon influenced the European dragon in design and creation. It is possible that Marco Polo brought back information on dragons after his travels, which were during the late 1200's and early 1300's. But it is never mentioned in his Travels of Marco Polo diary account of his trip. But regardless, it can't be denied that the Chinese developed their dragons to a high degree of detail, far earlier than the Europeans, who were only producing rudimentary dragon artwork at this time.

We haven't even had any depictions of European dragons up until this point. It is from here that we first start to see the mention of European dragons in the culture.

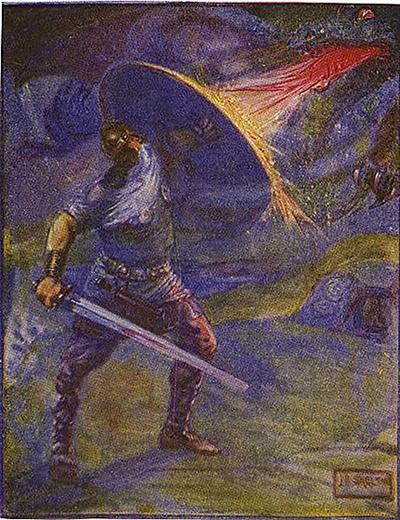

Of Beowulf and Dragons

Even though there are no illustrations from the period of Beowulf to show what contemporary people thought the dragon would have looked like, here is a 1908 illustration by J. R. Skelton, which is as far removed from any modern interpretations as I could find in reference to Beowulf specifically.

"He heeded not the fire, though grievously it scorched his hand, but smote the worm [dragon] underneath, where the skin failed somewhat in hardness."

Beowulf

Similar to the gryphon, cyclops, and Amazonians from before, the bones of dinosaurs are thought to be the basis for the dragon mythology. Ancient people would find the bones and build legends around them, much like they did in ancient Rome and Greece. However, in this instance the beasts that were created became dragons, with an ever expanding array of features like fire breathing, armored skin, and wings. Unlike dragons of modern day though, the dragons on the middle ages appeared more "worm-like" as mentioned in the Beowulf text. As we continue on through the middle ages, this will become more pronounced.

Dracorex at the Children's Museum of Indianapolis, photo by David Orr

One fossil find that is even named after dragons because of it's uncanny resemblance to what we know of today as dragons is the pachycephalosaur Dracorex.

Although not discovered until 2003, it is unlikely that this specific species of dinosaur was the source of the dragon mythology. But it is not out of the realm of possibility that other similar fossils sparked the medieval imagination.

The next few posts will follow the "evolution" of dragons through the Middle Ages to see how they have "evolved" in medieval culture.

References

http://shc.stanford.edu/news/research/dinosaurs-and-dragons-oh-my

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dragon_(Beowulf)#/media/File:Beowulf_and_the_dragon.jpg

https://www.flickr.com/photos/anatotitan/5098486930/

Dragons in the Early European Medieval Ages

I was recently having a conversation about dragons and I was asked if it could honestly be said that dragons evolved through local discoveries of dinosaur bones. And while, it can not be absolutely proven that dragons stem from dinosaurs (it's likely not even possible that scientists could prove one way or the other that they are linked), I think it is a safe assumption that there is some historical linkage between the two.

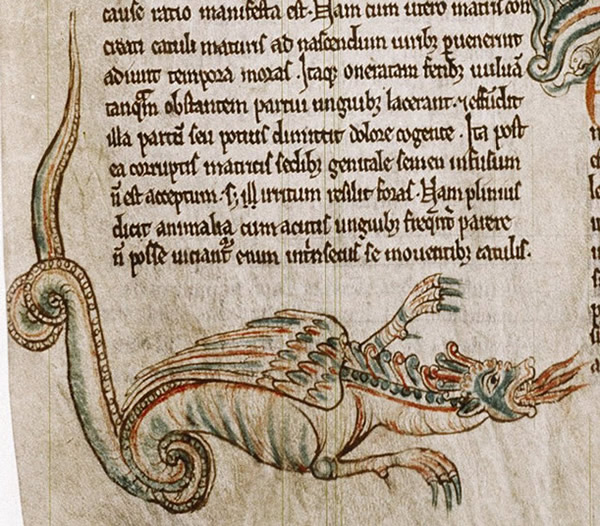

Even though much writing and other information has been lost from the Medieval Ages, there are still some sources available about what people thought about dragons during that time. During this period it is unclear though if the myth of dragons had stemmed from the discovery of more dinosaurs, or had slowly been evolving on its own, building upon itself as time went by. Good websites to find information on Medieval beasts is The Medieval Bestiary and the British Library. These websites have some crossover between them and are a good check on the sources. Images below can be found at this link: http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beastgallery262.htm#

I cannot find many examples of dragons in the 1100's or earlier. But the dragons during this time period are depicted to be rather small. They have a dog-like appearance, however with only hindlimbs (no front limbs) and large wings (compared to their body size).

1100's dog-like dragons found in the Bodleian Library, MS. Ashmole 1462(De medicina ex animalibus).

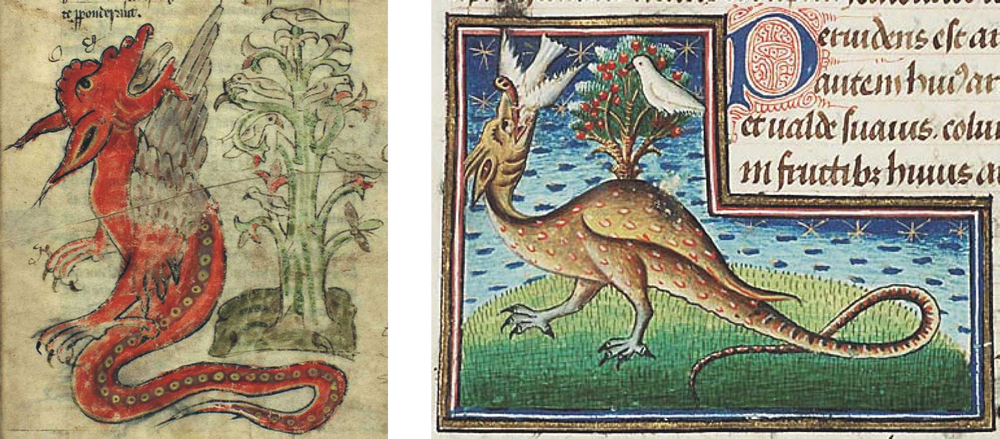

Dragons in the Middle European Medieval Ages

As time continued into the 1200's, a feature of dragons that was common during this time was their morphological characteristics. More often than not, they were portrayed with large wings, large rear legs, no front limbs at all, and large ears. Their general body shape was elongate/worm like with enlarged torsos. The one thing that has evolved in them since the 1100's is that they are now depicted much larger, often depicted in association with elephants to emphasize this. Their ears and hind legs have also grown in proportion to the body, as compared to the previous century.

1250's document showing the size similarities of dragons and elephants. This image can be found in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, lat. 14429.

In some myths, the dragon took on the embodiment of Satan, where in this instance the doves are Christians trying to be protected from being devoured. The tree is referred to as a Peridexion tree and can be seen a few times in the literature. The image on the left can be found in the Bibliothèque Municipale de Douai, MS 711 (De Natura animalium) and the one on the right from the British Library, Harley MS 3244.

Some more dragons near some Peridexion trees. The image on the left can be found in the Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon, MS P.A. 78 (Bestiaire of Guillaume le Clerc) and the image on the right can be found in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, fr. 1444b (Bestiaire of Guillaume le Clerc).

Another version of the dragon showing the "standard" Medieval morphological features. This image can be found in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, lat. 6838B,

A different version of a dragon with two sets of wings and legs. I assume, based on the preponderance of only legged dragons during this time, that the front set it not meant to represent front limbs, rather another set of hind limbs. This image can be found in the British Library, Harley MS 3244.

Another dragon, presented much the same as those above except this one is shown in comparison to an elephant to illustrate its size. This image can be found in the British Library, Sloane MS 278 (Aviarium / Dicta Chrysostomi)

This image I found to be rather peculiar compared to the previous ones. The hind limbs have almost taken on a front limb characteristic, and the illustration seems to have much more detail and colors than the others. This image can be found in the Bodleian Library, MS. Douce 167.

Sung Dynasty (969 AD - 1279 AD)

The entire Nine Dragons handscroll created by Chinese artist Chen Rong from 1244. Click on the image for a full sized view.

One of the dragons on the Nine Dragons handscroll created by Chinese artist Chen Rong from 1244. I wanted to emphasize the detail in some of the dragons shown on the scroll so I picked out two of them. These are some of the best but by no means the only ones.

Another dragon on the Nine Dragons handscroll created by Chinese artist Chen Rong from 1244.

~1260 AD

St. George and the Dragon

A few years ago I was invited to give a talk in St. George, Utah. I had chosen a version of my "Dinosaurs! From Cultural to Pop Culture" to give to the audience when a friend of mine asked if I was going to include the story of St. George and the Dragon, knowing that I had a heavy dragon component to the talk. At the time my talk was pretty well set and I hadn't heard of St. George and the Dragon, so I let it go to be researched another day. That day has come.

The story of St. George and the Dragon is a convoluted one through history. Aspects of the story were written far later than the real St. George's life, added to, and adapted from other sources. The primary source for the story of the dragon appears to come from the Legenda Aurea written in approximately 1260 by Jacobus de Voragine. The story goes, that there was a dragon which was terrorizing a town. The people satiated the dragon with sheep. However when sheep alone wouldn't satisfy the dragon anymore they started adding people into the mix with the sheep. And when that didn't work anymore it became multiple people at a time. Until one day the king's daughter was the sacrifice. Despite all he tried, the people would not let the king get away without sacrificing her. He ended up sending he along to the dragon's lair to be sacrificed for the sake of the town. Well, when she was standing outside the dragon's home, the man who will eventually become known as St. George happened to pass by.

St. George was a good Christian proselytizer who lived during the 3rd century AD. He was born in Cappadocia, which eventually became Turkey, but he was eventually killed by Emperor Diocletian for refusing to give up his Christian faith, a faith handed down to him through his parents. However, that it not the primary reason he is remembered today. He is known for his dragon tale.

After St. George passed by the princess, he decided to take on the dragon to save the princess' life.

"Thus as they spake together the dragon appeared and came running to them, and S. George was upon his horse, and drew out his sword and garnished him with the sign of the cross, and rode hardily against the dragon which came towards him, and smote him with his spear and hurt him sore and threw him to the ground. And after said to the maid: Deliver to me your girdle, and bind it about the neck of the dragon and be not afeard. When she had done so the dragon followed her as it had been a meek beast and debonair."

After defeating the dragon, St. George dragged it back to the town where he promised to kill the dragon if everyone converted to Christianity. Upon everyone's conversion, St. George killed the beast and "smote off his head."

12th Century icon of St. George and the dragon from Likhauri, Georgia. Image is in the Public Domain.

Early works of art depict St. George sitting triumphantly upon a horse with a spear point towards the ground. No dragon is to be seen. Later works though, began to incorporate the dragon at the base of the horse. The earliest work that I could find with the dragon is this 12th century icon of St. George and the Dragon from Likhauri, Georgia. This image of the dragon followed the cultural norms of the time, showing the dragon in a snake-like form with feathery wings and long, pointy ears.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Legend

https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/goldenlegend/GL-vol3-george.asp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_George_and_the_Dragon

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kondakov_1890._St_George_icon_from_Likhauri.jpg

Dragons in the Middle European Medieval Ages

As mentioned before a good website to find information on Medieval beasts is The Medieval Bestiary. Another good source is the British Library, which has some crossover between the sources and is a good check on the sources. Images below can be found at this link: http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beastgallery262.htm#

Dragon's in the 1300's continued along the very familiar lines of the 1200's. Here is depicted a dragon at the base of the Peridexion tree, with the same physical attributes as before. These include the large hind legs, big ears, and wings, although this particular example appears to not have any wings present. This image can be found in the Bodleian Library, MS. Bodley 912.

More images of dragons from the 1300's. These are interesting in that they appear to have feathers or fur of some variety. In the 1200's some of the dragons appeared to have some feathers on their wings but not to the degree that these show. The left image is of a dragon supposedly licking somebody, although to me it looks like it is vomiting. Both images can found in Bodleian Library, MS. Douce 308.

These dragons also feathers, but only on their bodies. With the feathers they also have bat-like wings. Both images can be found in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, KB, KA 16.

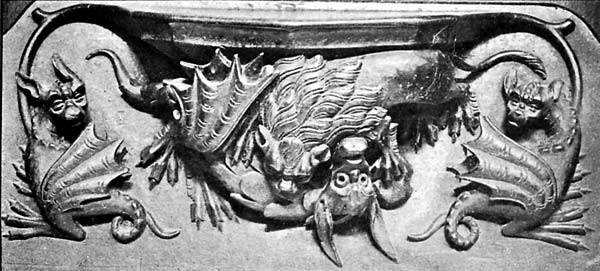

The above image is of a wood carving of a bat with four legs, which is rare but not unheard of from the 1200's. This bat also shows leathery bat wings instead of the bird like wings of the drawings. This carving is from the Cartmel Priory, from Cartmel, England and the image can be found in Wood Carvings in English Churches: Misericords by Francis Bond (1910).

Yuan Dynasty

Yuan Dynasty dragon hanging scroll ink painting (The Met).

Dragon images on a Yuan Dynasty porcelain pot (cultural-china.com).

Dragons in the Late European Medieval Ages

There is a continued stagnation of dragon development through the end of the Middle Ages, although the drawings do seem to get more detailed.

More dragons at the base of the Peridexion tree. The interesting item of note here, is that the dragon on the left appears to have something running down the midline of its back and tail. Hard to tell what they are supposed to represent although they do look like octopus suckers. Perhaps they supposed to be spikes? This isn't a one off occurrence either as can be seen in a dragon illustrated below with the same circle pattern. The image on the left is from the Kongelige Bibliotek, Gl. kgl. S. 1633 4º (Bestiarius - Bestiary of Ann Walsh). The image on the right is from the Museum Meermanno, MMW, 10 B 25.

More of the same types of dragons as before, though often in more detail. The dragon on the left does have that circular pattern running down its tail too. Perhaps it is no coincidence that both images are from the same book, the Kongelige Bibliotek, Gl. kgl. S. 1633 4º (Bestiarius - Bestiary of Ann Walsh). The well feather specimen on the right is from the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, KB, 72 A 23 (Liber Floridus).

Here is a leathery dragon with the bat-like wings is from the Museum Meermanno, MMW, 10 B 25.

These carvings (also illustrated in the Wood Carvings in English Churches: Misericords by Francis Bond (1910) like the 1300's Dragon image above) can be found in the Carlisle Cathedral, Carlisle, England. As seen above, these dragons are pictured with more a bat wing appearance, however the other attributes remain the same.

Ming Dynasty

1402 - Nine Dragon Wall

The Nine Dragon Wall in Beihai Park, Beijing was built in 1402.

Close up of some of the dragons (Wikipedia).

Flask decorated with a dragon and wave scrolls in underglaze blue, Ming dynasty, 14th century. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Encyclopedia Britannica)

This is the end of our Eastern Dragons. From here you can see that dragons in modern day China greatly resemble, if not are identical, to many of the dragons being created over 500 to 1500 years ago. The dragons produced in China's history showed remarkable detail and exquisite design, in a style that has been imitated and matched for over 1,000 years.

1572 AD

The Last Dragon Slaying in Europe

Most of the dragons that appeared in the middle ages (AKA the Medieval Times) were fanciful beasts, often feathered, with wings and perhaps a couple of front legs. But they were clearly in the realms of people's imaginations brought about into life by some variety of artisan. This current "dragon" is a bit different, to the point that it is very debatable whether this could even be considered a "dragon" by the loosest stretch of the definition.

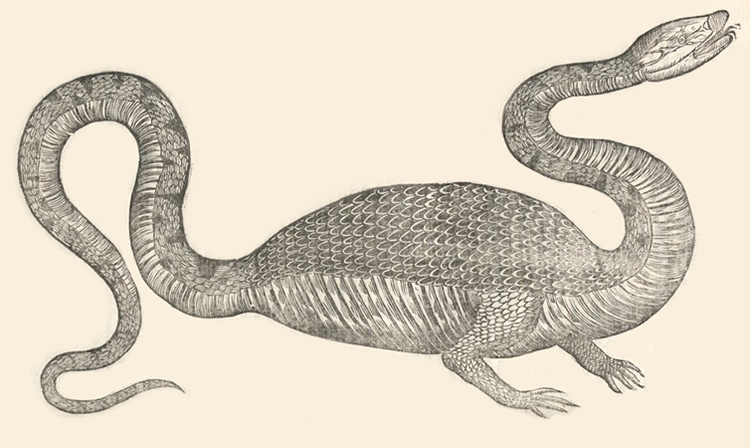

Drawing of the "dragon" in question by Ulisse Aldrovandi in the The Natural History of Snakes and Dragons (page 404), published posthumously in 1640.

It started in 1572 when a herdsman named Baptista of Camaldulus came across this beast that, as far as he knew, resembled a dragon near the town of Bologna.

"...the herdsman noticed a hissing sound and was startled to see this strange little dragon ahead of him. Trembling he struck it on the head with his rod and killed it."

Normally this would be written off as nutery, however the person who described the remains of this "dragon" was Ulisse Aldrovandi, a naturalist of some influence who had written many essays on the subject and had slowly built up a museum termed the Theatre of Natural Science in Bologna. Aldrovandi described the beast as reptilian that slithered along like a snake, however it used it's front limbs to help propel itself forward.

Compared with contemporary dragon illustrations there appears many similarities, however this dragon is notable for its lack of wings. Nearly every example of European dragons (at the time) were two legged, winged, reptilian beasts. And although Aldrovandi's illustration hits most of the salient parts, its lack of wings is noticeable. It may be assumed that Aldrovandi was a quack, or just wrote hearsay articles about dragons without any definite proof, so why put any stock in this image. However, he specifically states in his book where this dragon appears, The Natural History of Snakes and Dragons, that all of his dragons are presented as third-hand knowledge and he has had no direct knowledge of any dragons ... except this one. Why single out this one individual?

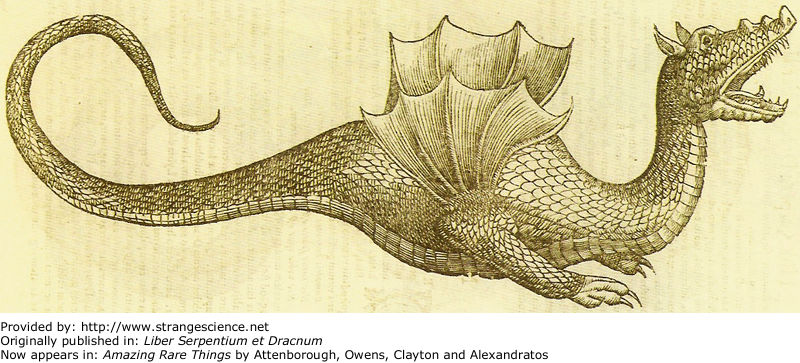

For example, here is another dragon illustration from the book, which is specifically of a dragon, not a personally described specimen. This dragon follows the body plan that was more or less laid out at the time.

Another dragon illustrated by Ulisse Aldrovandi in the The Natural History of Snakes and Dragons (1640). Image from StrangeScience.net.

As a scientist myself, I wonder if this is some exaggerated specimen of a snake that just ate a large meal, or perhaps a mutated snake with vestigial limbs. Being a naturalist I would assume that Aldrovandi would be able to identify a well fed snake versus a legitimately "fat" snake. This specimen was also apparently kept in his collection at the Theatre of Natural History for a long period of time until it was eventually lost (conveniently), likely sometime in the 1700's or 1800's. Perhaps it was all a hoax at our expense, the world may never know.

Although this would more than likely be classified as an oddity of biology and not a legitimate "dragon" (if it were indeed true), it was often referred to as the "last dragon" of Europe. And Aldrovandi himself referred to the animal as Draco Bononiensis (Bologna Dragon). So I place this here in our history of dragons as cultural influencers, as perhaps this species of animal, whatever it may be, may be our actual link to a dragon source.

References

https://mysteryinksite.wordpress.com/2016/09/25/the-last-dragon-mystery/

https://amshistorica.unibo.it/126

The History of Four-footed Beasts and The History of Serpents

by Edward Topsell

"Among all the kindes of Serpents, there is none comparable to the Dragon..." (Edward Topsell)

Illustration of some dragons from Edward Topsell's The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents (1658)

In 1607, Edward Topsell wrote The History of Four-Footed Beasts, shortly followed in 1608 by The History of Serpents. Both volumes were eventually combined in 1658 into The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents after Topsell's death. You can actually find a PDF of the book here at Archive.org to check it out yourself, but as far as I am aware the 1658 text is identical to the original text of 1607 and 1608.

The purpose of the volumes was to provide an accurate representation of animals that exist in the world, however Topsell relied on other people's accounts on what was real and what was fictional. It is my understanding that everything Topsell wrote, he believed was real:

"The second thing in this discourse which I have promised to affirm, is the truth of the History of Creatures, for the mark of a good Writer is to follow truth and not deceivable Fables."

Topsell wrote several items of note about dragons in his books as if they were real-life animals.

"The remedies or medicines coming from this beast are these: first, the flesh of them eaten, is good against all pains in the small guts, for it dryeth and flayeth the belly. Pliny affirmeth, that the teeth of a Dragon tyed to the sinews of a Hart in a Roes skin , and wore about ones neck, maketh a man to be gracious to his Superiors... I know that the tail of a Dragon tyed to the Nerves of a Hart in a Roes skin, the suet of a Roe with Goose-grease, the marrow of a Hart, and an Onyon, with Rozen, and running Lime, do wonderfully help the falling Evill, (if it be made into a plaifter.)" (Page 92)

There are many other recipes as well which call for "the head and tail of a dragon" or "the fat of a dragon's heart".

But this has to be my favorite account:

"There are Dragons among the Ethiopians, which are thirty yards or paces long, these have no name among the inhabitants but Elephant-killers. And among the Indians also there is as an inbred and native hateful hostility between Dragons and Elephants: for which cause the Dragons being not ignorant that the Elephants feed upon the fruits and leaves of green trees, do secretly convey themselves into them or to the tops of rocks: covering their hinder part with leaves, and letting his head and fore part hang down like a rope, on a suddain when the Elephant comcth to crop the top of the tree, (he leapeth into his face, and diggeth out his eyes, and because that revenge of malice is too little to satisfie a Serpent, (he twineth her gable like body about the throat of the amazed Elephant, and so strangleth him to death."

There are pages and pages about dragons once you get to the "On the Dragon" portion of the text (pages 701-716) if you want to check it out yourselves. But the most important part of the text is the illustrations (for my purposes). The sketches of the dragons in his book (above and below) aren't any better than dragon depictions from any of the previous Medieval works from the 1400's back through the 1100's.

Illustration of another dragon from Edward Topsell's The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents (1658)

Reading the text, you get why his illustrations resemble previous illustrations of dragons so much. It is because Topsell isn't coming up with any new information himself. He is just taking the information that had been created previously, thinking it is an accurate representation of what there was at the time, and passing it along in the guise of a factual encounter of real-life dragons.

References

1651 AD

The Mexican Dragon

Dragon illustration from the Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia (1651) by Francisco Hernandez [Page 816].

In the 1570's, a Spanish physician named Francisco Hernandez was tasked to travel through Mexico and document the plants and animals for the region with the intent of publishing a tome with this information. His trip was funded and directed by King Phillip II, whom Hernandez was the physician for. King Phillip II was intent on expanding Spanish influence on scientific matters in the world by directing the first European scientific exploration of the "New World". Hernandez ended up traveling through Mexico for three years with the help of the local Aztecs, constantly cataloging plants and animal species. He eventually spent a small fortune but the trip was considered a success with a boat load of specimens brought back to Spain.

Unfortunately, by the time of Hernandez's death in 1587, the tome wasn't even close to being published. Still wanting to make a profit on this knowledge, King Phillip II tasked another court doctor to finish the publication. Eventually, this new doctor and King Phillip II both passed away without making much headway. Part of the issue was that Hernandez's notes were confusing and jumbled up, adding to the difficulty in organizing them, especially for anyone who wasn't on the trip in the first place. He also often used the local name for species of plants and animals, not knowing how they related to European plants and animals.

In 1603, some of his notes were eventually discovered by Federico Cesi, a member of a high-class Italian family. Being fascinated with the papers, Cesi spent a small fortune obtaining all of the scattered Hernandez papers that he could find. He then tasked himself and his friends, which included a young Galileo, to organizing and eventually publish this tome. Years went by and all of Cesi's friends who were working on the publication eventually passed away, except for one, Francesco Stelluti. Stelluti was finally able to bring the final document to publication in 1651, eighty years after Hernandez initially set out to the New World. The finalized work was entitled Nova plantarum, animalium et mineralium Mexicanorum historia (New Plants, Animals, and Minerals Mexican History).

With so many people touching this manuscript from the time of Hernandez's journey until final publication it is impossible to know which illustrations were original to the author and which were added later. The illustration itself also looks like it was pieced together from several different animals with the head and body of a snake, and the scaled wings unlike anything that I am aware of. I have seen people claim that this illustration, or others like it, is evidence of pterosaurs still in existence, however the body structure and wing plans are nothing like any pterosaur that I aware of. The body structure however does resemble previous dragon illustrations throughout the history of the middle ages in Europe. Specifically like the dragons from Topsell's The History of Four-footed Beasts and The History of Serpents. This strong similarity lends credence that this dragon is completely made up, probably by one of Cesi's crew of workers.

References

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/francisco-hernandez-the-coolest-explorer-youve-never-heard-of

https://www.strangescience.net/stdino2.htm

1696 AD

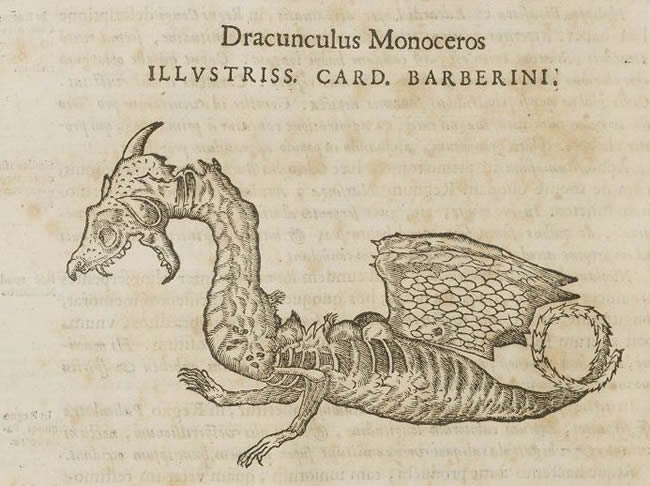

Cornelius Meyer's Dragon

Towards the end of the 1600's, Europe was still enmeshed is dragon fever, with dragons still commonly being thought of as real life animals. Nothing portrays that better than the case of Cornelius Meyer's dragon (or Cornelio Meyer as it is inscribed on the skeleton placard). The case of the dragon was excellently laid out in a 2013 publication by Phil Senter and Pondanesa D. Wilkins (Senter and Wilkins, 2013).

Skeletal display of the dragon as presented by Meyer in his 1696 book.

In 1691, Cornelius Meyer "discovered" a dragon skeleton while excavating for a dike in the vicinity of Rome. The dragon had apparently plagued the landscape, being the blamed as the cause for much of the flooding that Rome was experiencing. The dragon was assumed to have been killed in 1660, however there was debate about the issue, and the dragon was re-assumed to be alive. The locals were skeptical of pissing off the dragon by constructing the dikes, so the dragon needed to be dealt with first.

In order to allay the fears of the local populace, Cornelius Meyer went out to "take care of" the dragon, which he so conveniently produced the body of for public display. The image above is an illustration of the skeleton that was put on display with the caption "Drago come si ritrova nelle mani dell' Ingegniero Cornelio Meyer" (“Dragon as it was recovered in the hands of the engineer Cornelius Meyer”).

Reconstruction of the dragon based on the associated skeleton from Meyer's 1696 book.

The image of the skeleton, as well as the reconstruction drawings were reproduced for a book authored by Meyer, Nuovi ritrovamenti Divisi in Due Parti (New Findings Divided in Two Parts), which was published in 1696. The book is mostly a description of dike construction projects in the vicinity of Rome with just a few brief images of the dragon and its reconstruction. Very little information is given in the text about the dragon itself.

Another reconstruction as presented by Meyer in his 1696 book.

This particular dragon was recently brought back into the public conscious as evidence that pterosaurs and humans once coexisted. To quell that idea, Senter and Wilkins went about to describe the specimen as it is presented by Meyer in the skeletal reconstruction. Based on comparative anatomy, they were able to deduce that the skeleton was indeed a hoax (assuming a real skeleton was ever actually presented as it is illustrated). From their scientific analysis they determined (pretty conclusively in my opinion) that the skull was that of a dog, the mandible a smaller dog, the hind limbs were of a juvenile bear's forelimbs, the ribs were from a large fish, and the tail, wings, and nose horn were all fake additions. The skeleton was also presented with "advantageous" skin coverings which hid the joints between the disparate parts.

I find that the most interesting aspect of the dragon is the continuation of the medieval body plan of the dragon being dragged almost into modern day society. We still continue to see the prevalence of two hind limbs, leathery wings, an elongated fat leathery body, long tail, and a dog-like face. So much dog-like that the skull was determined to be an actual dog! The body itself also appears to be rather small, given that the skull was of a dog. I would estimate that the entire body would only likely be about 10 feet from snout to tail tip and a few feet high standing upright. In general, although they somehow reigned terror in the Middle Ages, they were only about the size of a large lion at the most.

References

And that is it with out look at dragons in the Medieval Age. Shortly after the reign of dragons we get into the proper scientific discoveries of dinosaurs and how the understanding of their fossils have influenced our pop culture in the...