Idaho

Type |

Symbol |

Year Est. |

|---|---|---|

State Gem |

Star Garnet |

1967 |

State Fossil |

Hagerman Horse Fossil (Equus simplicidens) |

1988 |

State Gem: Star Garnet

TITLE 67

STATE GOVERNMENT AND STATE AFFAIRS

CHAPTER 45

STATE SYMBOLS

67-4505. STATE GEM DESIGNATED. The star garnet is hereby declared to be the official state stone, or state gem, of the state of Idaho.

History: [67-4505, added 1967, ch. 33, sec. 1, p. 56.]

Prior to being polished, the star garnet will be found with the same dodecahedral crystal pattern found in other garnets. Image courtesy of IdahoStarGarnet.com.

Garnet is typically thought of as one specific mineral, however garnet is actually a series of very similar minerals. This mineral series varies in chemical composition, resulting in different mineral names, however the chemical composition of all of the garnets share a generalized chemical composition: X3Y2(SiO4)3, where "X" can be Ca, Mg, Fe2+, or Mn2+, and "Y" can be Al, Fe3+, Mn3+, V3+, or Cr3+. Along with the different chemical compositions, there are different colors and hardnesses associated with each one as well. Crystals of garnet typically form in 12-sided "balls", that can be easy to identify within the rocks that they are found in. The name "garnet" comes from the Latin, "granatus" meaning "like a grain" because of this ball-crystal habit. Garnet is formed from the metamorphism of shale minerals, and can be found in most foliated metamorphic rocks such as schist and gneiss. Garnets can also be found in some igneous rocks including granites and granitic pegmatites. Garnet has been used as a gemstone since ancient Egypt, however recently garnet has obtained significant usage as an abrasive. Since garnet is a rather hard mineral and has no cleavage, it typically breaks into sharp edged fragments, and therefore produces a good grit for water-jet cutting or sandblasting. Garnet is a very common mineral and even high grade gemstone quality specimens can be fairly cheap.

A polished example of a star garnet. Image courtesy of Geology.com

The Star Garnets are a rare variety of garnet which contain an "asterism", which is the star effect across the surface of the gem. This feature is more commonly seen in sapphires and rubys as well as other minerals. The star effect is caused by the inclusion of the mineral rutile within the garnet crystal. Star garnets are typically a deep brownish-red or reddish-black, producing almost a purplish hue. After careful polishing, the alignment of the rutile produces a reflection of light that produces a 3-dimensional star light pattern. The most common stars are the 4-rayed star (as pictured), however a 6-rayed star is possible, although very rare. The Star Garnet has most commonly been found in India and Idaho, however small amounts have also been found in Russia, Brazil, and North Carolina. Within Idaho, Star Garnets are found in the northern parts of the state near St. Maries, an area known as the Emerald Creek Garnet Area. The public is allowed to collect here for a small permit fee.

Related: Connecticut State Mineral - Almandine Garnet; New York State Gem - Garnet; Vermont State Gem - Grossular Garnet

State Fossil: Hagerman Horse Fossil (Equus simplicidens)

TITLE 67

STATE GOVERNMENT AND STATE AFFAIRS

CHAPTER 45

STATE SYMBOLS

67-4507. STATE FOSSIL DESIGNATED. The Hagerman Horse Fossil (species Equus simplicidens originally described as Plesippus shoshonensis) is hereby designated and declared to be the state fossil of the state of Idaho.

History: [67-4507, added 1988, ch. 44, sec. 1, p. 50.]

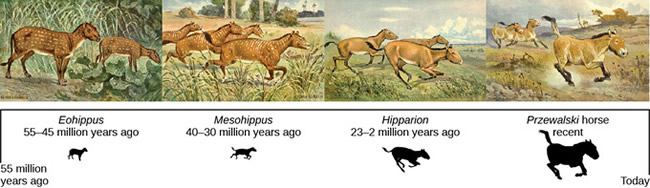

Some select representations of horse species over the past 55 million years. Image courtesy of Biology LibreTexts.

Horses are one of the modern day species that has a remarkable fossil history. One of the earliest known relatives to modern day horses is the species Hyracotherium, more commonly known as eohippus or the "Dawn Horse" (although there is some scientific debate about whether Hyracotherium and Eohippus are two distinct species are just different examples of the same species). Hyracotherium lived around 55 million years ago and was about the size of a modern dog, much smaller than modern day horses. Evolutionarily, horses are within the order Perissodactyla, which are the odd-toes ungulates. This means that horses and their relatives, tapirs and rhinoceroses, typically have one or three toes. Hyracotherium was initially adapted for tropical forests, however as the landscape slowly dried and cooled over time, new horse species evolved to be adapted for the dryer, prairie habitat. With the development of the prairies approximately 20 million years ago, the new horse species were larger and more adapted for grazing. Over the last 55 million years, over 50 species of horses evolved, with lineages often branching and living coevally, however the only horse genus left alive today is Equus, which includes not only horses but zebras and donkeys as well.

.jpg)

Fossil of the Hagerman horse, Equus simplicidens, from the Hagerman Fossils Beds National Monument Visitor's Center.

Among the myriad of horse species that have evolved was the species known as the Hagerman horse, Equus simplicidens. The Hagerman horse, first named in 1892 by Edward Drinker Cope, is the oldest known species of Equus. Equus simplicidens lived during the Ice Age, specifically the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs, approximately 1.8 to 3.5 million years ago. Despite the name, the Hagerman horse is actually closely related to a modern day zebra, Grevy's Zebra (Equus grevyi). It is known from fossils all over North America, however the densest concentration of fossils is in Idaho where over 200 individuals had been found at Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument. The fossil beds are comprised of two distinct bone beds, one of which was thought to be a periodically dried up river. There is some debate about how the horses died, but one theory is that the horses came here to drink, but upon finding the water not there died of thirst. Seasonal rains then came in, swept the horses up, and piled them upon a riverbank, where they were then covered over with sediment and eventually fossilized. Another theory is that the horses were killed during a flood while trying to cross the river. However, because so many of the horses were found within one location, it has helped scientists to determine that these horses were likely herd animals.

References

https://statesymbolsusa.org/states/united-states/idaho

https://legislature.idaho.gov/statutesrules/idstat/title67/t67ch45/sect67-4505/

https://www.minerals.net/gemstone/garnet_gemstone.aspx

https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~adg/adg-pgalimages.html

https://www.minerals.net/gemstone/almandine_gemstone.aspx

https://geology.com/minerals/garnet.shtml

https://www.gemselect.com/english/other-info/about-star-garnet.php

https://visitidaho.org/travel-tips/digging-for-idahos-star-garnets/

https://geology.com/gemstones/states/idaho.shtml

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/fossil-horses/gallery/hyracotherium

18%3A_Evolution_and_the_Origin_of_Species/18.5%3A_Evidence_of_Evolution/

18.5E%3A_The_Fossil_Record_and_the_Evolution_of_the_Modern_Horse

https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/horse/the-evolution-of-horses

https://www.nps.gov/hafo/learn/nature/simplicidens.htm

http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/e/equus-simplicidens.html

Geology of Idaho's National Parks

Through Pictures

(at least the one's I have been to)

City of Rocks National Reserve

Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve

Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument

Minidoka National Historic Site

City of Rocks National Reserve

Visited in 2015

Our last stop on our tour of southern Idaho national parks was the City of Rocks National Reserve. At the City of Rocks, it is possible to travel through the whole park in essentially one loop, however you must leave the park on the western edge to get between the northern and southern roads of the park. We decided to take the southern road first, following the available Automobile Tour, then loop around to the northern road to finish the park.

.jpg)

It had been a long trip, so I ended up not getting out of the car for this one. But snapped the picture as I drove by regardless.

.jpg)

During our trip we followed the "Automobile Tour" and my wife had read about each of the stops along the way. This is Circle Creek Basin. The main part of the rocks are from a 28 million year old granitic dome named the Almo Pluton, which is the lighter colored granitic rocks. The darker brownish-gray rocks are the Green Creek Complex (a complex mainly consisting of granite, granitic gneiss, and schist), which is 2-3 billion years old and are some of the oldest rocks in North America.

.jpg)

Treasure rock, where we let our daughter get out for the first time to "go play on the rocks".

.jpg)

View of the most prominent feature of the park, the Twin Sisters and Pinnacle Pass (on the left half of the photo). This is the pass through which the California Trail followed. The left twin is made up of Green Creek Complex, and the right is Almo Pluton.

.jpg)

Side view of the Twin Sisters focusing on the Green Creek Complex sister in the foreground. The other twin is actually directly behind the formation with only the tip of it peaking over the center of the photo. The outcrop on the left half in the background is not one of the twins (I think).

.jpg)

Dike through the Almo Pluton.

.jpg)

This was the last picture before having to leave the park on the western edge to complete our loop on the northern road. You can see the natural jointing of the rocks in the background lining up with the eroded arch in the foreground.

.jpg)

A rock formation lovingly called the Bread Loaves showing more jointing in the granitic pluton. This is the first formation after we came back into the park on our loop.

.jpg)

The northern part of the part had a lot more rock formations than the southern part and in general was much prettier. If you can only do part of the park, I recommend this part.

.jpg)

Here is Window Arch, which is probably the best hike in the park. Especially for people with a 5 year old who can't walk that far.

.jpg)

The pathway up to Window Arch, through the Almo Pluton.

.jpg)

Some nice jointing in the Window Arch area.

.jpg)

Back along the road, on our way out looking into the City of Rocks, where it indeed looks like a bunch of "buildings" sticking up out of the ground.

Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve

Visited in 2012

We had taken a trip to visit one of the nearby parks in southern Idaho.

.jpg)

My standard park sign picture, but this time with the little one.

.jpg)

Here is a lava tube entrance. Craters of the Moon is located within a region of the US known as the Snake River Plain. The Snake River Plain was created as the North American plate slid of over the Yellowstone Hotspot. A hotspot is a volcano that stays in one place while the plates slide over it, like Hawaii.

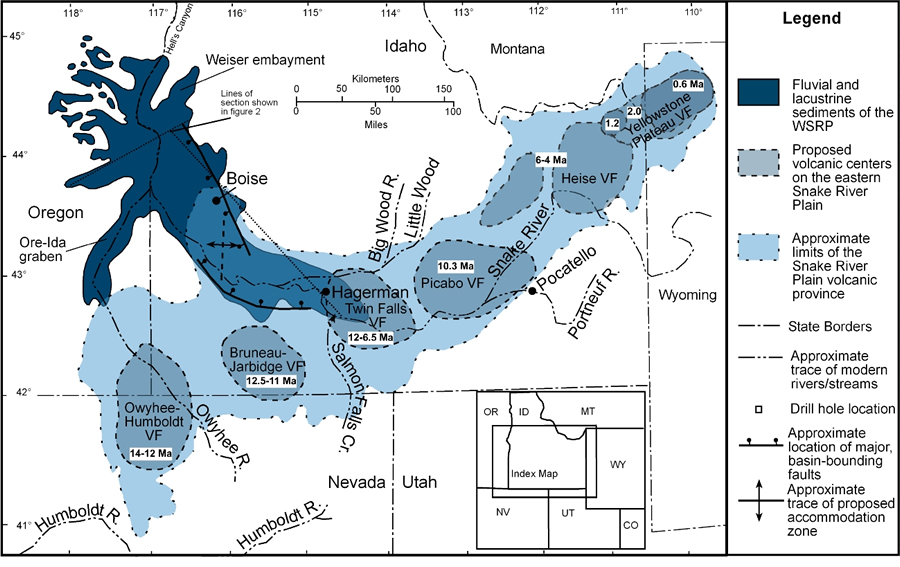

Pathway of the Yellowstone Hotspot across Idaho. Image courtesy of the Digital Geology of Idaho. Craters of the Moon falls to the northwest of the Picabo Volcanic Field, which is dated to 10.3 million years ago. This is the time when the Yellowstone hotspot was located at this point and had erupted. However, the volcanic activity that we see at Craters is not directly related to the Yellowstone hotspot.

.jpg)

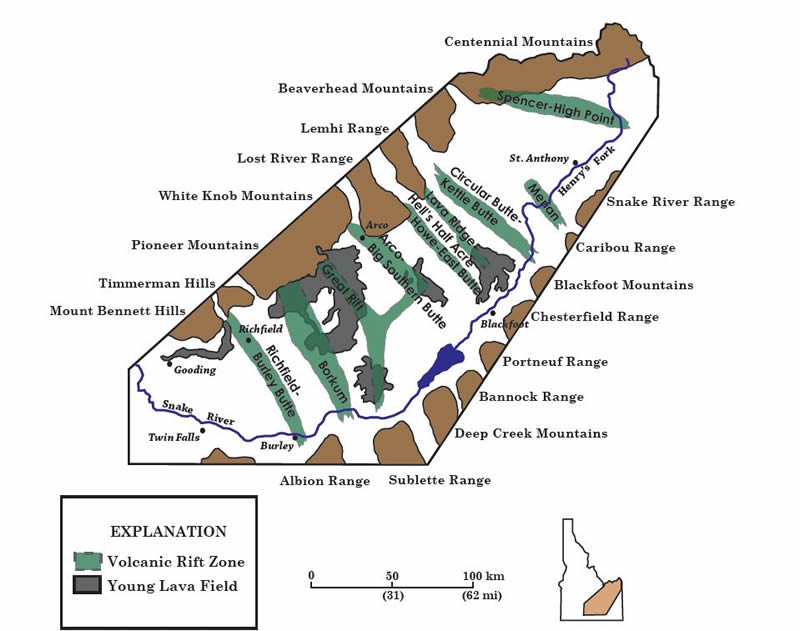

At Craters we can see the result of that volcanic activity by the remnants of lava flows, lava tubes, and other volcanic features. Here we can see a pretty good view of the landscape that has many trees and shrubs but is still pretty barren. There are three separate lava fields within the National Park that range in age from 15,000 years to 2,000 years old, all far younger than the 10.3 million year old Picabo eruption. Craters of the Moon is found along a track of land known as the "Great Rift".

.jpg)

Within the are there are a lot of dead trees hanging about. The Great Rift is an area of crustal thinning associated with the expansion of the Basin and Range area, as well as deflation of the crust following the passage of the hotspot. So, although the volcanic activity is not a direct result of the Yellowstone hotspot, it still played a role. The combined effect of the crustal thinning and the deflation produced areas of increased volcanic activity, with one of the largest areas being Craters of the Moon.

The above shows multiple rift zones within the Snake River Plain. The large grey areas aligning with the Great Rift represent Craters of the Moon. Image courtesy of the NPS.

.jpg)

Within the region remains a lot of extinct volcanoes including this cinder cone. A cinder cone is a volcano that is created by the eruption of lava blocks that eventually pile up to create this rather steep sided pile of rock. He we are climbing up the largest of the cinder cones, Inferno Cone.

.jpg)

Panoramic view from the top of Inferno Cone.

.jpg)

View from Inferno Cone of a couple of smaller cinder cones.

.jpg)

Another view of the same lava flow, this time a little further up. You can see both types of basaltic lava flows here, pahoehoe and 'a'a. Pahoehoe lava is the smooth lava, that often has a ropey texture, while 'a'a lava is a more blocky, sharp lava. 'a'a' lava was named for the sound people made when walking across it barefoot. Here you can see a nice transition from the pahoehoe to the aa style lava.

.jpg)

Some nice 'a'a, splatter lava.

.jpg)

View of an 'a'a lava flow showing large chunks of volcanic rocks.

.jpg)

A lava tube is formed when flowing lava starts to solidify when it is contact with the air, eventually forming a crust on the lava flow. The crust continues to build up as the lava continues to flow through the tube, eventually forming this open space within the lava flow. Here I am entering one of the lava tubes.

.jpg)

Some nice ribbon pahoehoe lava. I really love the fine cracks that run perpendicular to the ribbon folds.

.jpg)

View looking out of one of the larger lava tubes, Dewdrop Cave.

.jpg)

Within the largest lava tube in the park, Indian Tunnel. Several places along the length of the tube, the ceiling has caved in giving visitors a nice walk even without the need of a headlamp.

References

http://geology.isu.edu/Digital_Geology_Idaho/Module11/mod11.htm

https://www.nps.gov/crmo/learn/education/upload/CRMO-PDF-Complete.pdf

https://volcanohotspot.wordpress.com/2016/05/26/craters-of-the-moon-idaho/

Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument

Visited in 2015

As we continued our tour through southern Idaho, I really wanted to visit Hagerman, not the least because I am a paleontologist. Well, let me just get this out of the way first off, I saw no fossil localities, unlike at Dinosaur NM or Fossil Butte NM. This is more of a preserve to protect the fossils but they don't have the infrastructure (yet?) to allow the public access to see the actual dig sites. Hopefully that will come along sometime in the future. But as a paleontological National Park, this is the weakest one I have been to.

.jpg)

Me and my Gummy Bear doing our sign thing.

.jpg)

When we were planning on going to the park, I read everywhere that we had to go to the Visitor's Center first. Well this is the first thing that we noticed upon walking up to the door.

.jpg)

So as most any paleontologist is wont to do, we started digging to see what we could find.

.jpg)

Inside they also had a nice display full of fossils and other geological specimens for the kids to play with and analyze.

.jpg)

And they also had some of the more common mammal fossils.

.jpg)

Along with fossils found within the park too, like this lovely horse, Equus simplicidens, the State Fossil.

.jpg)

And some elephantine specimens

.jpg)

After leaving the Visitor's Center there is one road with a couple of view spot's along it. This one describes the changing landscape from the Pliocene, when the fossils are from, to today.

.jpg)

There are also remnants of the Oregon Trail, as seen here with the trail ruts.

.jpg)

And here you can see them really well on the left side of the photo where the road bends.

.jpg)

The Snake River Plain, where Hagerman is located, is known for its volcanic landscape. As the North American Plate traveled westward, the plate was dragged across the Yellowstone Hot Spot. The hot spot melted a swath through the Idaho countryside that left a significant mark on the landscape. The remnants of the old shield volcanoes and lava flows are pervasive throughout the region, as is described in this display.

Minidoka National Historic Site

Visited in 2015

Minidoka was the first stop on our tour of southern Idaho national parks. The Minidoka National Historic Site was the place of one of the former Japanese "internment camps" that was erected during World War II. Although, not a geological park there are some geological elements to the park.

.jpg)

My lovely daughter presenting our NP sign.

.jpg)

Some background information on the Relocation Center.

.jpg)

One of the few remaining original structures. The building materials for these structures was almost exclusively the local vesicular basalt (basalt with a lot of holes in it). The basalt was formed in the Snake River Plane when the Yellowstone Hotspot (volcano) was located within Idaho. The hot spot hasn't actually moved, but the North American plate has moved westward across the hot spot, creating this volcanic valley through Idaho, now known as the Snake River Plain.

.jpg)

A close up view of one of the vesicular basalt blocks.

.jpg)

View of the Internment Camp fence with the nearby Clover Creek running alongside it. Clover Creek is a tributary of the Snake River. The residents of the internment camp created a pool out of the water from the creek since the creek itself was too fast to allow for safe swimming.

.jpg)

Panoramic shot of the park and the region along one of the park trails. Mostly flat within the Snake River plain. Footprints of the former buildings are visible along the way.

Visited in 1997 and 2010

For all of the pictures from Yellowstone National Park be sure to head over to the: