Arizona

Type |

Symbol |

Year Est. |

|---|---|---|

State Gemstone |

Turquoise |

1974 |

State Fossil |

Petrified Wood (Araucarioxylon arizonicum) |

1988 |

State Metal |

Copper |

2015 |

State Gemstone: Turquoise

CHAPTER 55

House Bill 2109

AN ACT

RELATING TO STATE GOVERNMENT; PROVIDING THAT TURQUOISE BE THE STATE GEMSTONE, AND AMENDING TITLE 41, CHAPTER 4.1, ARTICLE 5, ARIZONA REVISED STATUTES, BY ADDING A NEW SECTION 41-858.

Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of Arizona:

Section 1. Title 41, chapter 4.1, article 5, Arizona Revised Statutes, is amended by adding a new section 41-858, to read:

41-858. State gemstone·

TURQUOISE IS THE OFFICIAL STATE GEMSTONE.

A piece of turquoise from Madagascar. Image courtesy of carionmineraux.com.

Turquoise is a blue-green mineral made up of copper, aluminum, and hydrous phosphate (CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)). The name turquoise comes from the French expression for "Turkish Stone", illustrating that the early sources for European turquoise were from the Middle East. Turquoise has long been considered valuable and is one of the oldest known gemstones. It has been found in ancient Egyptian and Chinese archeological expeditions, showing that those people used turquoise as far back as 3,000 years ago. It is formed by the flowing of groundwater through copper deposits that eventually react with phosphate and aluminum minerals. Turquoise is also only found in arid (desert) environments because that is one of the few places that allows the groundwater to maintain a high enough copper concentration for long enough to interact with the other minerals. The result is a gemstone unlike traditional, gemstones like ruby or emerald, which is most commonly opaque. The opaqueness is due to the structure of turquoise, which is made up of many microcrystalline structures instead of one large mineral crystal. These microcrystals give the turquoise its appearance, either a mottled look or a smooth finish, which is due to the size of these microcrystals. It is also extremely soft and easy to carve. All of these attributes make it useful for many different purposes from jewelry to architectural adornments.

Spiderweb turqouise jewlery. Image courtesy of Durango Silver.

Turquoise mines can be found all across the southwestern United States, with the largest concentration found in Arizona. As mentioned above, turquoise mines in Arizona are often associated with copper mines (many of them open-pit mines in AZ). The largest and most well known of the turquoise mines is the Bisbee Mine, near Bisbee, AZ, located adjacent to the Copper Queen copper mine. In 1880, the mine was founded as a gold, silver, and copper mine, which are often found together due to the formation of these minerals from the waters associated with subduction zone magmatism. The hydrothermal waters associated with the former subduction zone in the region circulated throughout the rocks depositing the heavy metal deposits within the bedrock. These heavy metal deposits eventually interacted with the local groundwater producing these turquoise deposits. The Bisbee Mine turquoise was discovered in the 1950's and quickly became prized for it's spider-webbing patterns throughout the turquoise stones (pictured left). Although most of the turquoise has been mined out, this has resulted in these variety of the gem to become prized collectors items. Native Americans (primarily the Anasazi and the Hohokam) mined the turquoise in Arizona for use in jewelry and for trade. Arizona is also home to one of the largest domestic turquoise mines, located in Kingman.

Related: Nevada State Semi-Precious Gemstone - Turquoise; New Mexico State Gem - Turquoise

State Fossil: Petrified Wood (Araucarioxylon arizonicum)

CHAPTER 88

SENATE BILL 1455

AN ACT

RELATING TO STATE GOVERNMENT; PROVIDING FOR ADOPTION OF PETRIFIED WOOD AS THE

OFFICIAL STATE FOSSIL, AND AMENDING TITLE 41, CHAPTER 4.1, ARTICLE 5, ARIZONA REVISED STATUTES, BY ADDING SECTION 41-853.

Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of Arizona:

Section 1. Title 41, chapter 4.1, article 5, Arizona Revised Statutes, is amended by adding section 41-853, to read:

41-853. State fossil

PETRIFIED WOOD, OR ARAUCARIOXYLON ARIZONICUM, IS THE OFFICIAL STATE FOSSIL.

.jpg)

Petrified wood from Petrified Forest National Park. Image taken by me.

Petrified wood is not actual wood, however it was wood at one point. Petrified wood is a fossil that formed from pieces of wood that have been mineralized. Mineralization is a process where groundwater moves through the wood and replaces all of the wood molecules with molecules of other substances, most often silica (i.e. quartz). This means that petrified wood actually isn't wood anymore, but a fossil of the former wood.

The specific species of petrified wood (Araucarioxylon arizonicum) that is the Arizona state fossil is an extinct conifer (like an evergreen) that can been found throughout Arizona and New Mexico. There is a problem with the state fossil though; the original name of the species was based on three different species. This means that although one of the three was correct, two had to be renamed, resulting in several of the trees identified since the initial 1889 description were likely named incorrectly. The problem is that proper identification can only be made with thin sections and close analysis, which is not likely going to happen for a majority of the samples previously identified, at least not any time soon. Arizona is host to one of the largest assemblages of petrified wood logs, with ~20% of all the petrified wood in northeastern Arizona found in Petrified Forest National Park. The concentrations of logs in Petrified Forest was a result of a log jam that flowed down a prehistoric river. The logs where then quickly buried, which allowed the mineralization process to proceed on the logs, converting them into fossils.

Related: Louisiana State Fossil - Petrified Palmwood; Mississippi State Stone - Petrified Wood; North Dakota State Fossil - Teredo Petrified Wood; Texas State Stone - Petrified Palmwood; Washington State Gem - Petrified Wood

State Metal: Copper

CHAPTER 77

S. B. 1441

AN ACT AMENDING TITLE 41, CHAPTER 4.1, ARTICLE 5, ARIZONA REVISED STATUTES, BY ADDING SECTION 41-860.03; RELATING TO STATE EMBLEMS.

Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of Arizona:

Section 1. Title 41, chapter 4.1, article 5, Arizona Revised Statutes, is amended by adding section 41-860.03, to read:

41-860.03. State metal

COPPER IS THE OFFICIAL STATE METAL.

An example of native copper.

Photo courtesy of the Flandrau Science Center at the University of Arizona.

Copper is an elemental metal mineral, meaning that it is entirely composed of one element; copper (Cu) in this instance. It is also the only elemental metal, besides gold, which is not naturally silver or grey. Copper is the oldest known metal to have been manipulated by humanity. The Copper Age took place after the Neolithic (Stone) Age, and lasted from ~4500 BC to ~3500 BC, overlapping with the early Bronze Age. The earliest known Middle Eastern artifact is also made of copper, a pendant dating back to 8700 BC. In the modern day, copper is the third most consumed industrial metal in the world. Mining of copper in the US began with high grade ore deposits found in Arizona and Michigan in the late 1800's, however newer processes that were able to filter the copper out of low-grade deposits made excavating low-grade ores more economical, leading to more abundant uses of strip and open-pit mining for the recovery of copper. These processes enabled the US to become one of the leading producers of copper in the world.

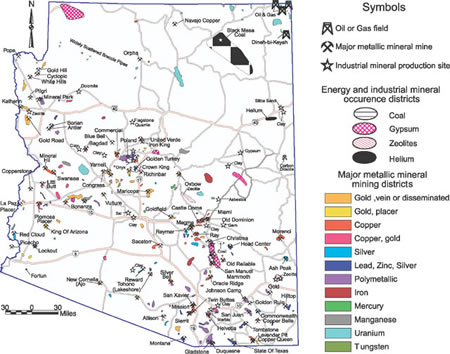

Arizona's metallic mining map from the Arizona Geological Survey.

In the late 1600's, Spanish explorers traveled the west looking for metallic deposits, specifically gold and silver. The association of these metals with copper enabled them to discover numerous copper deposits as well, even though it was not their primary focus. Eventually, the modern age of mining in Arizona was born in 1854 with the creation of the Arizona Mining and Trading Company in Ajo, AZ. Mining for copper was initially restricted to deep mine tunnels of fairly high quality ore. However, the success of the open-pit Bingham Mine in Utah illustrated that open-pit mining and new processing methods for low-grade copper ore worked well and Arizona began using similar processes, increasing their copper yield significantly. Currently, copper is the most valuable metallic commodity in Arizona, followed by gold, silver, molybdenum, and lead. In 2017, the US produced 1.27 million tons of copper with 68% of that coming from Arizona. There are currently over 3,000 Arizona locations that have copper listed as a commodity. These metallic deposits form a northwest to southeast band across the state (as seen on the map to the left). Along this band, most of the copper deposits are found within southeastern portion of the state (red on the map). These deposits are found mostly in granitic rocks that intruded within the region 70 to 55 millions years ago.

Related: Utah State Mineral - Copper

References

https://statesymbolsusa.org/states/united-states/arizona

http://www.azsos.gov/public_services/kids/kids_state_symbols.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turquoise

http://www.turquoise-museum.com/arizonaturquoisemines.htm

http://www.turquoisemines.com/bisbee-turquoise-mine/

https://www.durangosilver.com/spiderweb-turquoise-cabochons.html

http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/gemstones/sp14-95/turquoise.html

http://indianvillage.com/arizonaturquoisemines.htm

http://www.traderoots.com/Turquoise_About.html#Introduction

http://www.carionmineraux.com/mineraux_avril_09.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Araucarioxylon_arizonicum

http://waynesword.palomar.edu/pfnp.htm

http://www.nps.gov/pefo/index.htm

http://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub362/item1495.html

https://www.livescience.com/29377-copper.html

https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2018-coppe.pdf

https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/azsession/id/12/rec/6

https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/azsession/id/4/rec/9

https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/azsession/id/86/rec/10

Geology of Arizona's National Parks

Through Pictures

(at least the one's I have been to)

Canyon de Chelly National Monument

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

Hohokam Pima National Monument

Petrified Forest National Park

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument

Tumacácori National Historical Park

Walnut Canyon National Monument

National Parks visited but I have no pictures (at this time) to do a geology post

(link directs to NPS site)

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (2012)

Canyon de Chelly National Monument

Our final park this trip, after a shortened visit to Petrified Forest and needing to skip another park entirely was Canyon de Chelly, which we ended up staying the night at the park hotel. Because of the snowstorm, the roads ended up being a bit hit or miss, with the lower elevation roads practically snowless and the higher elevation roads nearly impassable.

.jpg)

The entrance sign. The name of the canyon is a Spanish corruption of the Navajo word "Tsegi" meaning rock canyon. The pronunciation of "de Chelly" has slowly morphed over time from the Spanish "day shay-yee" to the modern day pronunciation of "d'SHAY".

.jpeg)

Canyon de Chelly is a unique park, since it is an actively lived in park. The park is run in conjunction with the Navajo Nation, where members of the Navajo Nation also live in the park and actively help preserve the ancient cliff dwellings within the walls of the canyon. The park is composed of several canyons, the primary two being Canyon de Chelly (the southern canyon with views from the road facing north) and the northern canyon, Canyon del Muerto, with views towards the south. The two canyons split off from each other towards the visitor's center.

When we arrived in the evening, we were advised to do the southern rim drive, along Canyon de Chelly, first. Then hold off and do the northern rim drive, along Canyon del Muerto, in the morning to get the best light in both. This is a view from Tunnel Overlook up the end of the Canyon de Chelly before the Canyon del Muerto splits off.

.jpeg)

A little bit further along the canyon, this is a view across the Canyon de Chelly from the Tsegi Overlook.

.jpeg)

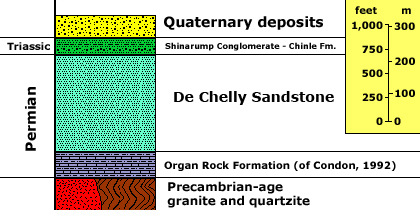

View from the next stop at Junction Overlook. The canyon is made up almost entirely of one rock unit, the De Chelly Sandstone, which is a Permian age (~200 million years old) aeolian sandstone. Aeolian means that it is formed by blowing wind, in particular sand dunes, or a desert environment. When sand dunes are frozen in time, such as when they become rocks, and eroded you can see features termed cross-bedding. These rock preserve an ancient desert that used to be located here. We will look a little bit more into cross-bedding in a later photograph below.

A cross section of the Canyon de Chelly National Monument geology from the USGS. Although most of the canyon walls are composed of sandstone, there is a bit of the Triassic age Shinarump Conglomerate along the tops of the cliffs and the older Permian Organ Rock Formation along the base of the canyon.

.jpeg)

View from the White House Overlook, looking down on the White House cliff dwelling. Many of the cliff dwellings on the southern side are not as easily seen from the road, however we can get a closer look at some of the later houses.

.jpeg)

Here is the Face Rock overlook with the cliff dwellings located within the center of the cliff face in the center of the photograph.

.jpeg)

A zoomed in view of the Face Rock cliff dwellings. These, and most of the cliff dwellings in the park, were built between 1100 and 1300 CE by the ancestral Puebloan people before the arrival of the modern day Navajo. This time period corresponds with other cliff dwellings in the region such as Mesa Verda and Tonto National Monument.

.jpeg)

Along the Canyon del Muerto on the northern part of the park there are not as many overlooks but the views of the cliff dwellings are far better. This is the first stop along the northern rim at Antelope House Overlook with Antelope House below the cliff on the right part of the image.

.jpeg)

Here is a closer up view of Antelope house. The buildings were constructed using a combination of the De Chelly Sandstone as building blocks and adobe bricks that were created from the mud and baked.

.jpeg)

View from the Mummy Cave overlook. The cliff dwellings are located along the left side of the photo.

.jpeg)

Close up view of the Mummy Cave cliff dwelling.

.jpeg)

Yucca Cave cliff dwellings.

.jpeg)

View up Canyon del Muerto at Massacre Cave Overlook.

.jpeg)

View at the Massacre Cave Overlook with the cross-bedding in the De Chelly Sandstone highlighted by the snow. The cross-bedding is the angular lines through the sandstone layers. While here the layers of sandstone are generally horizontal, the cross-bedding is at an angle. The way cross bedding forms within a dune is illustrated below:

As sand is pushes up over a dune by the wind, the sand grains form parallel lines on the slipface of the dune. These parallel lines of the grains are what we see preserved within the rock. Image from Carleton.edu.

References

http://web.archive.org/web/20170220180015/https://www.nature.nps.gov/Geology/parks/cach/index.cfm

http://npshistory.com/newsletters/sw_mon_rpt/special-report_no_20.pdf

https://serc.carleton.edu/NAGTWorkshops/sedimentary/images/cross_bedding.html

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument

Visited in 2016

Although Casa Grande Ruins is mainly an archaeology park, there is geology everywhere. Even if sometimes it is just a pretty picture of the landscape. For Casa Grande Ruins we learn how settlers in the land used the land, even as inhospitable as it may seem, to their advantage.

.jpg)

My entrance sign picture

.jpg)

The Casa Grande (big house), which is being protected from the elements via a giant tent structure. As a building which was built over 650 years ago, it's looking pretty good. Some other structures and the base of walls from structures long ago are in the foreground.

.jpg)

As can be read on the sign, the ancient Sonoran people used caliche (pronounced ka-lee-chee), which is a calcium carbonate rich desert soil. The caliche was then collected, then mixed with water and formed into the walls while wet. Once dried, the walls have lasted centuries.

.jpg)

A close up view of the front of the house. You can clearly see the difference between the fixed areas (along the base and around the door) and the original areas.

.jpg)

The back side of Casa Grande

.jpg)

Looking up into Casa Grande.

.jpg)

Several of the outlying buildings are partially intact as well. The is one of the structures to the south of Casa Grande.

.jpg)

Looking north towards Casa Grande.

.jpg)

A view of the Sonoran Desert with a Sonoran Desert People's "ball pit" located in the foreground. As you can see, there is not much in this desert environment. Even cacti are not that prevalent.

.jpg)

View of the Casa Grande with one of the old signs and a saguaro cactus.

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

Visited in 2009

.jpg)

For all of the pictures from Glen Canyon National Recreation Area be sure to head over to the:

Visited in 2011

.jpg)

The entrance sign.

.jpg)

This is our first view of the canyon. We went during the middle of March. Not a good time to go apparently.

.jpg)

But it did eventually clear up. This is a similar location as the previous picture on a subsequent day.

.jpg)

Some elk by our hotel room.

.jpg)

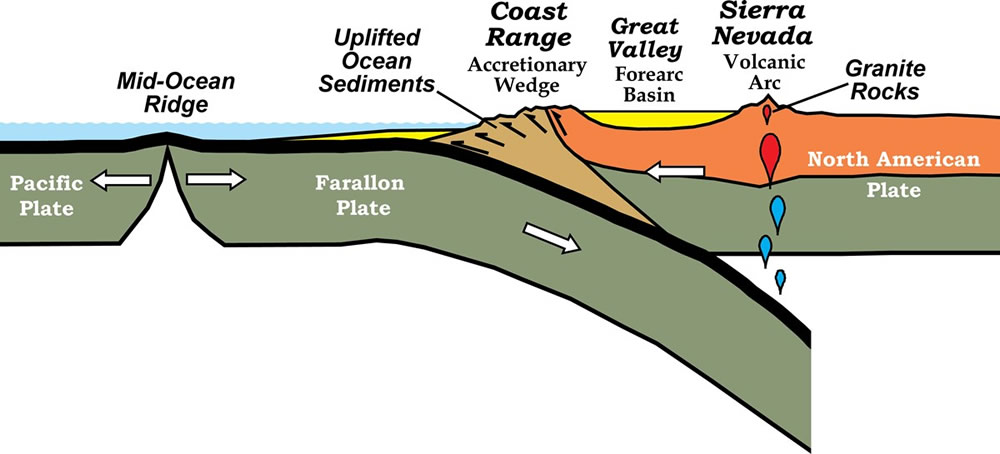

View off into the canyon. The canyon began to be formed due to plate tectonics. There used to be a subduction zone off the western coast of California (where the San Andreas Fault is now). The plate that was subducted, the Farallon Plate, was forced down underneath North America. This plate was hot and therefore force the North American Plate upwards. The upward push of the plate was counteracted by the Colorado River eroding down through the plate. The upward motion of the plate allowed the river to erode downward faster and deeper than it otherwise would have.

.jpg)

The rock units that were eroded through range in age from fairly recent to over a billion years old. The types of rocks are limestones, sandstones, shales, as well as several metamorphic and igneous rocks. The result is a huge range of bright colors represented in the canyon.

.jpg)

Here I am trying to get a vertical view of the canyon.

.jpg)

The cloud formations across the surface here made the landscape really look pretty.

.jpg)

Here is a panoramic view of the canyon.

.jpg)

Another panoramic view.

.jpg)

Along the rim they have these markers designating the passage of geologic time. I walked all the way back to the beginning to get the first one.

.jpg)

A cool train station within the park.

Here are a few of Grand Canyon National Park. The flight was from Salt Lake City to Phoenix back in October of 2016, which happened to perfectly line up with the Grand Canyon.

.jpeg)

As mentioned above, the Grand Canyon is a massive erosional feature formed through the movement of the Earth's crust known as Plate Tectonics. Here, we are mainly focused on the interaction of the North American plate and the Farallon plate.

Off the west coast of North America used to be a plate called the Farallon Plate. It was being subducted (going beneath) North America for several millions of years until the majority of the plate had been completely subducted. This recently subducted plate was rather hot and therefore pushed upwards on the overriding North American Plate. Image courtesy of the NPS.

.jpg)

As the Farallon Plate traveled below North America, the upward force of the hot plate pushed up a section of North America known as the Colorado Plateau. Surface features, such as rivers, are then locked in place as the ground surface moves upwards, the rivers start to erode more and more downwards. This creates features such as the Grand Canyon and things called "entrenched meanders" where formerly meandering rivers are locked into place as they are now eroding downwards in that meander shape. Image courtesy of Written in Stone.

.jpeg)

Here is an entrenched meander of the Colorado River. The Colorado Plateau has several entrenched meanders, besides just the one in the image above including at Natural Bridges National Monument.

.jpeg)

As erosion within the canyon deepened, it also widened. This created one of the largest canyons on Earth seen here at the Grand Canyon. Although one of the largest canyons on Earth, the Grand Canyon is not THE largest. There are several larger canyons, specifically in areas where similar processes are occurring by the significant uplift of the ground surface, such as along the Himalayan Mountains.

.jpeg)

Hohokam Pima National Monument

This is a very bizarre "park" just south of Phoenix, AZ. When you try to find out any official information on the park, the park website either doesn't exist or it simply says "The area is not open to the public". When I asked at the nearby Casa Grande Ruins NM about this park they told me it wasn't a real park at all and never was formed into a park. However the park is on the NPS website, and on all maps and fliers that list all the parks officially published by the NPS. From what I can find out, this park is officially on a Native American Reservation and it is not open to the public. The park was an ancient ruin, similar to Casa Grande Ruins, however instead of fully excavating them and displaying them, they were buried again after excavation to preserve them. So, even if you could gain access to the "park" there wouldn't be anything to see anyway.

Well, long story short, the official park property crosses over Interstate 10, and it was in the official part of the "park", where I stopped and grabbed a panoramic shot.

Photo looking west over the rest of Hohokam Pima National Monument during sunset.

Petrified Forest National Park

Visited in 2019

Following our visit to Tonto National Monument, we stayed the night in Winslow, AZ just as a massive snow storm struck the region. This forced us to change our plans a bit. The snow storm ended up closing most of Petrified Forest National Park, however we were able to at least hike along the Giant Logs Trail at the southern entrance while we waited for the gates to the rest of the park to be opened. They ended up never opening after several hours of waiting so we had to take the long way around the park without ever actually traveling through the park as planned.

.jpg)

The entrance sign during the blizzard.

.jpeg)

A view up the Giant Logs Trail, showing how many of the logs there really are. Each of those boulders is a part of a petrified tree. This area really is littered with the remains of the enormous petrified trees. The logs here are preserved within a rock unit called the Sonsela Member of the Chinle Formation, a rock unit that spreads throughout much of the Southwestern United States.

.jpeg)

Here is a view from up on top of one of the hills, looking down towards the visitor's center. A petrified log, is really just a fossilized tree. These particular logs lived ~216 million years ago, during the Late Triassic Period. When they died, they fell into a river, becoming buried under sand, silt, mud, and volcanic ash. After they were buried the cells of the tree were eventually replaced with silica (quartz) that was within the groundwater. Over time all of the original organic material was replaced with the silica, leaving behind the fossils.

.jpg)

After fossilization, the petrified trees are no longer organic, they are essentially rocks completely composed of silica. Normal, organic trees, when broken will break into long splinters. However, these trees are broken as if someone came through with a chainsaw and neatly chopped up the trunks of the trees. This happens because when silica breaks, it will often break along these smooth surfaces, especially when it is in the elongated form that is in here. These trees are harder than the surrounding landscape so they resist weathering creating these mounds which the trees sit upon. But over time, the ground surfaces are eroded beneath the trees and as the trees start to feel the pressure of gravity they are pulled down, eventually breaking under the pressure.

.jpg)

The colors within the petrified wood are created from the mixture of minor amounts of contaminants within the silica body. The contaminants are mostly comprised of iron and manganese. The iron produces the yellow, orange, reds, ochres, and black colors while the manganese produces the blue, purple, brown, and black colors.

.jpeg)

Some of these trees are truly massive in scale. The base of this tree, named Old Faithful, which still preserves some of the roots is around 5 feet across. Although, in today's park, the park would let these fossil succumb to the natural elements, back in the day that wasn't always the case. You can see here a concrete pad was placed under the tree to help prevent future collapsing of the base.

.jpg)

The amount of detail preserved in the trees in truly astounding as well. Here you can see several of the knots within the trunk still preserved.

.jpg)

And here we have the traces of insect burrows through the wood preserved (the vertical lines here through the horizontal wood grains).

.jpeg)

A gorgeous petrified log.

.jpeg)

View down a slope with several of the petrified logs in view.

.jpg)

Cross section of one of the logs, highlighting the colors within the rock. The detail preserved within the petrified logs is so fine that often scientists can still count the tree rings from the original trees to determine the ages and environmental conditions within which these trees initially lived.

Visited in 2019

On our 2019 tour of the deserts of the southwest we started outside of Tuscon at Saguaro National Park. The National Park is divided into two distinct districts. One to the west of Tuscon (the Saguaro West Tuscon Mountain District), which I'll just refer to as the West District, and one to the east (the Tuscon East Rincon Mountain District), which I'll refer to as the East District. We started out in the West District and ended the day in the East District.

.jpg)

Although we started in the West District, the sign for Saguaro in the East District was far better, so I'm placing that as my entrance sign pic.

.jpeg)

Here we started taking a hike through parts of the West District. Saguaro National Park is located within the Sonoran Desert, one of the largest deserts in North America. The Sonoran Desert is the second largest hot desert in North America, extending from Arizona into California and Mexico. It is also the hottest desert in Mexico, while the Mojave Desert holds the record for the hottest in the United States.

.jpeg)

The soil of this region is formed from the easily eroded sedimentary rocks overlying the surrounding mountains. The desert environment of extreme heat during the day followed by freezing cold at night causes the softer sedimentary rocks to expand and contract, breaking them down over time. Heavy summer rains then move these broken up rocks into alluvial fans adjacent to the mountains and into the plains. The ground surface is then covered by a rock known as caliche, which is a calcium carbonate rock formed from the leaching of the calcium from nearby limestones. The caliche ends up forming a crust on the surface that slows water from entering the soil. Shallow root systems help absorb any available water before it is lost to evaporation or percolation through the rocky soil. Caliche is often misinterpreted as dinosaur bones due to the white, roundish quality of the rocks.

.jpg)

Although Saguaro is a rather large National Park, it has limited access by vehicles, only having one short road loop in each district. There are several short hikes along each loop though. Here we took a hike up Signal Hill, which had some terrific petroglyphs located at the top of the hill.

.jpeg)

The rocks of Signal Hill and the surrounding country are a granodiorite from the Amole Pluton, which is an intermediate rock with a composition between the common igneous rock granite and its quartz poor cousin diorite. Granodiorite is a course grained rock (meaning we can easily see the mineral crystals) that initially formed deep in the earth from a magma body that slowly cooled at the end of the Cretaceous. This area used to be littered with active volcanoes and it is thought that the region looked similar to modern day Yellowstone. Later plate tectonic extension, a process that had formed the Basin and Range region of the American west, caused these deeply buried rocks to be raised to the surface in the Tuscon region.

.jpeg)

Although not directly geological, the petroglyphs are influenced by geology. These petroglyphs were created by people of the Hohokam culture between 450 and 1450 CE (in the common era).

.jpeg)

The petroglyphs were formed from engraving within the desert varnish on the surface of the rocks. Desert varnish forms on the surface of exposed rocks, frequently in the desert, from the accumulation of oxidized minerals of iron and manganese. These iron and manganese varnishes produce a darker, blackish rind to the rock. The minerals are accumulated on the surface by bacteria and lichen that live on the rock. The bacteria and lichens are anchored to the rock by clays particles in the atmosphere that precipitate out every time that it rains, taking with it manganese and iron particles. The bacteria and lichens then oxidize the iron and clay turning the varnish black. The more it rains, the more varnish is added to the rock. It is in this rind that the petroglyphs were carved.

.jpeg)

Unlike pictographs, which are painted on and can be washed away unless in a protected area, petroglyphs have the potential to be preserved for a long time after. Over time, the varnish layer will eventually cover over the pictographs when left to its natural processes.

.jpeg)

Within the desert, the landscape is dominated by rocks and water retaining plants because a desert, by definition, receives on average less than 10 inches of precipitation in an entire year. The Sonoran Desert averages between 3 and 15 inches per year, varying locally due to elevation differences and whether you are close to, or far away from the local mountains.

.jpeg)

As we exit the park in the northeastern portion of the West District we come across the Safford Dacite seen here. This deposit is a gray to light-brown lava flow from the early Oligocene (with different flows aging ~40 to 26 million years ago).

Following our exit from the West District, we proceeded to the East District on the opposite side of Tucson.

.jpeg)

We entered the park towards sunset, so most of our photos were centered on the setting sun.

.jpeg)

Although located fairly closely to the West District, the East District contains rocks that are much, much older. What we are looking at here are Precambrian granodiorite and quartz monzonite rocks from the Wrong Mountain Quartz Monzonite that are ~1.5 billion years old. Monzonites are igneous rocks with a lot of feldspar and relatively little quartz, however this rock has enough quartz to be termed a "quartz monzonite" (greater than 5%). With a large abundance of feldspar, that makes the monzonite relatively softer than other igneous rocks like granite and easier to erode over time.

.jpeg)

Within the igneous Wrong Mountain Quartz Monzonite are banded metamorphic rocks known at the Catalina Gneiss. This beautiful outcrop also has an age of ~1.5 billion years old and represents some higher amounts of metamorphism, altering the original monzonite, granodiorite, and other local igneous rocks.

.jpeg)

Another view of the Catalina Gneiss.

.jpeg)

And we leave you with this view of the sun setting to the west.

References

http://written-in-stone-seen-through-my-lens.blogspot.com/2013/12/petroglyphs-of-signal-hill-geology-and.html https://www.desertmuseum.org/books/nhsd_patternsrain.php

https://www.nps.gov/sagu/learn/historyculture/upload/Signal-Hill-Petroglyph-Brief.pdf

https://mikrogeo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/9e0da76350cdc15be25bb8bbb3437b14.pdf

http://npshistory.com/publications/sagu/nrr-2010-233.pdf

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument

Visited in 2011

.jpg)

View of the entrance sign with the volcano in the background.

.jpg)

The Sunset Crater Volcano is a volcano that last erupted about 1,000 years ago. It is a type of volcano known as a cinder cone, meaning that its eruptive material is small darkly colored rocks that pile up around the central vent. These rocks are typically a type of rock known as scoria, a vesicular (has lots of air holes in it), mafic (dark), volcanic rock. Since the last eruption was within the last 10,000 years, this volcano is still considered active by volcanologists.

.jpg)

Along with the cinder cone, there are also lots of lava flows within the park. Here you can see a lava flow that still looks as fresh as if it were a few years old. Since the desert environment does not get much rain, the volcanic rocks have a tendency to take a long time to break down, leaving these features for thousands of years.

.jpg)

Sunset Crater Volcano is part of a fissure eruption, which is a long crack in the ground that erupts like a volcano. Here the fissure runs along the left part of the photo ending at Sunset Crater Volcano in the middle of the photo.

.jpg)

Sunset Crater Volcano isn't the only volcano within the area or even within the park. There are lots of volcanos in this part of Arizona, mostly due to the plate tectonics of the area (as described in the Grand Canyon NP section above). The thinning of the crust due to the uplift of the plate causes weak spots in the crust where volcanic material can easily break through.

Visited in 2019

After traveling to Tumacácori NHS, we started to head north towards home. Along the way we stopped at a pretty picturesque park called Tonto National Monument that has a couple of cliff dwelling houses within a short hike of the Visitor's Center.

.jpg)

Obligatory entrance sign shot.

.jpeg)

The walls of the Visitor's Center were likely built using the local quartzite, which is the same formation which the cliff dwellings are located within and built from. By the looks of it, these Visitor Center bricks appear to be formed from the Lower Member of the Dripping Spring Quartzite, while the caves are located within the Upper Member. The Lower Member is composed of reddish brown sandstone and quartzite, while the Upper Member is composed of black, gray, red, and brown claystone, siltstone, sandstone, and quartzite.

.jpeg)

A view of the local geology surrounding the cliff dwellings. The caves are located within the Upper Member of the Dripping Spring Quartzite, while the majority of the hike took place on top of the Gila Conglomerate.

.jpeg)

View up the slope along the hike towards the Lower Cliff Dwellings. Looking up you can see the Upper Member of the Dripping Spring Quartzite, while we hiked up the slope of the Gila Conglomerate.

.jpeg)

As we hiked along you can see the chunks of rock within the Gila Conglomerate. The conglomerate often contained large, angular chunks of the Dripping Spring Quartzite. The ages of these two rocks also varied significantly. The much older Dripping Spring Quartzite formed from siltstones, sandstones, and dolomites that were laid down withing a shallow sea approximately 100 million years ago. The Gila Conglomerate, on the other hand, is the second youngest rock in the park and was formed from stream deposits that were slowly cemented over time by lime (caliche) that was left behind from evaporating water between 0.5 and 15 million years ago.

.jpeg)

Walking along the path we slowly come to the cave opening where the cliff dwelling resides. The caves are located within a section of the Upper Member of the Dripping Spring Quartzite that was especially susceptible to spalling (cracking or breaking into smaller pieces). As cracks started forming around sometime between 50,000 and 400,000 years ago, water carried away the pieces, enlargening the cave opening over time.

.jpeg)

The dwellings within the caves were built around 1300 CE (Common Era) by people of the Salado culture. They lived within these structures for around 150 years, while the climate slowly started to dry out, negatively impacting their agriculture. As life became more difficult, the people started to leave, completely abandoning the place around 1450.

.jpeg)

A view of some of the cliff dwellings. Unlike other local cliff dwellings like Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde which are built within sandstone, the quartzite blocks that broke off within this cave were too hard to shape and carve. So the dwellings were created by stacking quartzite blocks that were then covered with clay plaster.

.jpeg)

A view of some of the cliff front facing buildings. The caves faced east, which allowed the cliff dwellings to face the rising sun but then would soon be covered in shade in the hot summer sun, while in the winter the morning sun would warm up the cave after the cool nights.

.jpeg)

Turning around, here is the view out of the cliff dwellings towards the valley below with Theodore Roosevelt Lake in the distance, a man-made reservoir created from the local Salt River.

References

https://www.nps.gov/tont/learn/nature/geology.htm

Tumacácori National Historical Park

Visited in 2019

Following our trip to Sagauro National Park, we drove south towards the border to visit our next park, a small historical park preserving a local mission. Typically historical parks are limited on their geology, but there is always geology if you look hard enough.

.jpg)

The entrance sign.

.jpeg)

The family all excited to visit another park :-)

.jpeg)

The main church of the mission that remains standing today. The name Tumacácori (pronounced Too muh kä' koh ree) is interesting because it is a Spanish phonetic rendition of the local O'odham name for their local village. The source of the name in O'odham has been lost to time but it is though that it could mean "caliche hills" representing the desert limestone surface deposits in the area.

.jpg)

Built in the early 1800's, the mission is composed of adobe bricks and plaster. Adobe is a composite material of mud and plant material, often straw, and then baked in an oven. The plaster used was produced from the baking of local limestone, discussed more below.

.jpeg)

The central alter still preserves some of the original paint on the walls 200 years later.

.jpeg)

The outside of the main church.

.jpeg)

The remnants of the storeroom building.

.jpeg)

The lime kiln: where all the geology happens. At the kiln, limestone was loaded onto a heavy metal grate and then cooked over a fire. The limestone blocks would begin to swell and crack, at which point they would then be hammered into powder. The powder was then mixed with water creating a paste, and then mixed with sand producing the plaster. The plaster was then ready to be used on the local buildings.

The official source of the limestone was never recorded, however it is assumed to have come from the Santa Rita Mountains, some 25 miles away to the north. Doing some research of my own, I would say that a likely rock unit that the limestone came from was the Late to Middle Pennsylvanian (~300 million years old) Horquilla Limestone from the nearby Mt. Hopkins. Other than being one of the few limestone formations in the nearby mountain, it is also estimated at ~1,000 ft in thickness, making it an abundant source of limestone. The Horquilla Limestone is a fine-grained, medium- to light-grey limestone, interbedded with siltstone and conglomerate beds.

.jpeg)

Another view of the main church with the remains of some of the other buildings within the mission.

.jpeg)

The Tumacácori mission was located within the Sonoran Desert, which gets on average 3 to 15 inches of rain a year, making it one of the driest places in North America. So, one of the most important features within the desert landscape was the source of water. Here is the remains of the acequia, or irrigation ditch. This is where the mission would redirect the water from the neighboring Santa Cruz River.

References

https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0748/report.pdf

https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/b582

Walnut Canyon National Monument

Visited in 2011

.jpg)

Walnut Canyon is a archaeological site located within a geological site. The canyon itself is made up of several Colorado Plateau rock units that were impacted, like several other National Parks in the area, by the uplift of the Colorado Plateau. The canyon is capped with the Permian Kaibab Formation limestone, forming a layer resistant to erosion. The shelters created within the rocks are located within a shale and siltstone layer of the Kaibab Formation beneath this limestone roof.

.jpg)

Below the Kaibab Formation is the Coconino Sandstone and Toroweap Formation. These rock units are often difficult to differentiate from each other so they tend to blend together within the park.

.jpg)

Here you can see a view of the canyon with the alternating hard and soft rock formation.

.jpg)

View of the cliff dwellings built into the carved out section of the rocks.

.jpg)

Some more cliff dwellings.

.jpg)

And more cliff dwellings with a more complete wall located on the other side of the creek meander.

.jpg)

Following the trail around the houses, the trail goes back up the canyon.

.jpg)

Here is the Coconino Sandstone which underlies the Kaibab Formation. The cross-bedding is characteristic of the unit and illustrates the former desert dune history of the rock units.

.jpg)

A view of Walnut Creek, which carved out the canyon through the rock units. The cliff dwellings are located within the meander on the right side of the photo.

Visited in 2011

.jpg)

The obligatory entrance sign. The park is located on the edge of the San Francisco Volcanic field and the Painted Desert. This means that ancient people within the area likely had to contend with volcanic eruptions, as seen at the nearby Sunset Crater above, as well as the arid desert environment.

.jpg)

Here is a distant view of the Wupatki pueblo. Although mostly an archaeological park, there is tons of geology to be seen from all of the rock formations to the desert climate itself. The pueblos are built on top of and out of the Moenkopi Formation. These are sandstones, siltstones, and shales from a Triassic tidal environment (~240 million years old). This means that it was pretty close to the shoreline but also contained floodplain deposits.

.jpg)

Here is a closer view of the Wupatki Pueblo. The rocks in the Moenkopi have a high iron oxide content giving them a strong brown and red color to them.

.jpg)

Here is another of the pueblos, the Citadel Pueblo.

.jpg)

Closer, a little more abstract view of the Citadel Pueblo.

.jpg)

Close up view of the Moenkopi bricks.